1995年5月31日号「MAINICHI DAYLY NEWS」英語

「MAINICHI DAILY NEWS」に掲載された、祖母のインタビュー記事をご紹介します。

1

Kyoko Yamauchi : Kyoto’s living memory

Ed Gutierrez

Contributing Writer

Kyoko Yamauchi 山内京子

2

Kyoko Yamauchi has a genuine interest in other people and always likes to say after meeting someone that they are an ii hito or good person. Her openness and humor are infectious and visitors ranging from young students to university professors enjoy talking with her about a wide range of topics.

3

She’s both a sympathetic listener as well as a natural storyteller. Though she speaks in Japanese, even with her foreign guests of limited Japanese ability, she frequently has conversations which last hours and turn into late dinner parties. She’s also 87.

4

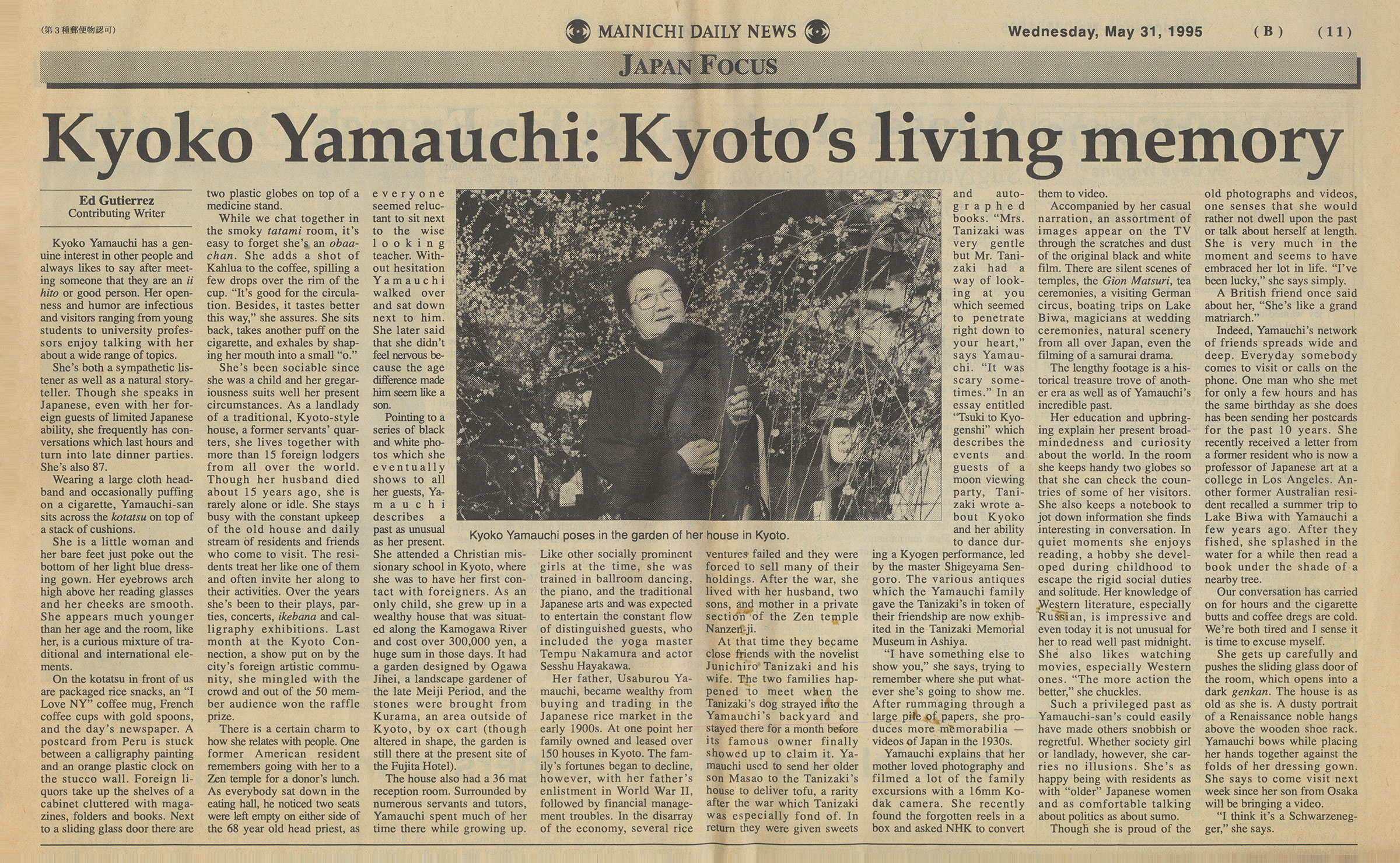

Wearing a large cloth headband and occasionally puffing on a cigarette, Yamauchi-san sits across the kotatsu on top of a stack of cushions.

5

She is a little woman and her bare feet just poke out the bottom of her light blue dressing gown. Her eyebrows arch high above her reading glasses and her cheeks are smooth. She appears much younger than her age and the room, like her, is a curious mixture of traditional and international elements.

6

On the kotatsu in front of us are packaged rice snacks, an “I Love NY” coffee mug, French coffee cups with gold spoons, and the day’s newspaper. A postcard from Peru is stuck between a calligraphy painting and an orange plastic clock on the stucco wall. Foreign liquors take up the shelves of a cabinet cluttered with magazines, folders and books. Next to a sliding glass door there are two plastic globes on top of medicine stand.

7

While we chat together in the smoky tatami room, it’s easy to forget she’s an obaa-chan. She adds a shot of Kahlua to the coffee, spilling a few drops over the rim of the cup. “It’s good for the circulation. Besides, it tastes better this way,” she assures. She sits back, takes another puff on the cigarette, and exhales by shaping her mouth into a small “o.”

8

She’s been sociable since she was a child and her gregariousness suits well her present circumstances. As a landlady of a traditional, Kyoto-style house, former servants’ quarters, she lives together with more than 15 foreign lodgers from all over the world. Though her husband died about 15 years ago, she is rarely alone or idle. She stays busy with the constant upkeep of the old house and daily stream of residents and friends who come to visit. The residents treat her like one of them and often invite her along to their activities. Over the years she’s been to their plays, parties, concerts, ikebana and calligraphy exhibitions. Last month at the Kyoto Connection, a show put on by the city’s foreign artistic community, she mingled with the crowd and out of the 50 member audience won the raffle prize.

9

There is a certain charm to how she relates with people. One former American resident remembers going with her to a Zen temple for a donor’s lunch. As everybody sat down in the eating hall, he noticed two seats were left empty on either side of the 68 year old head priest, as everyone seemed reluctant to sit next to the wise looking teacher. Without hesitation Yamauchi walked over and sat down next to him. She later said that she didn’t feel nervous because the age difference made him seem like a son.

10

Pointing to a series of black and white photos which she eventually shows to all her guests, Yamauchi describes a past as unusual as her present. She attended a Christian missionary school in Kyoto, where she was to have her first contact with foreigners. As an only child, she grew up in a wealthy house that was situated along the Kamogawa River and cost over 300,000 yen, a huge sum in those days. It had a garden designed by Ogawa Jihei, a landscape gardener of the late Meiji Period, and the stones were brought from Kurama, an area outside of Kyoto, by ox cart (though altered in shape, the garden is still there at the present site of the Fujita Hotel).

Ogawa Jihei,

the Fujita Hotel

11

The house also had a 36 mat reception room. Surrounded by numerous servants and tutors, Yamauchi spent much of her time there while growing up. Like other socially prominent girls at the time, she was trained in ballroom dancing, the piano, and the traditional Japanese arts and was expected to entertain the constant flow of distinguished guests, who included the yoga master Tempu Nakamura and actor Sesshu Hayakawa.

Tempu Nakamura 中村天風

Sesshu Hayakawa

12

Her father, Usaburou Yamauchi, became wealthy from buying and trading in the Japanese rice market in the early 1900s. At one point her family owned and leased over 150 houses in Kyoto. The family’s fortunes began to decline, however, with her father’s enlistment in World War II, followed by financial management troubles. In the disarray of the economy, several rice ventures failed and they were forced to sell many of their holdings. After the war, she lived with her husband, two sons, and mother in a private section of the Zen temple Nanzen-ji.

Zen temple Nanzen-ji

Usaburou Yamauchi

13

At that time they became close friends with the novelist Junichiro Tanizaki and his wife. The two families happened to meet when the Tanizaki’s dog strayed into the Yamauchi’s backyard and stayed there for a month before its famous owner finally showed up to claim it. Yamauchi used to send her older son Masao to the Tanizaki’s house to deliver tofu, a rarity after the war which Tanizaki was especially fond of. In return they were given sweets and autographed books. “Mrs. Tanizaki was very gentle but Mr. Tanizaki had a way of looking at you which seemed to penetrate right down to your heart,” says Yamauchi. “It was scary sometimes.” In an essay entitled “Tsuki to Kyogenshi” which describes the events and guests of a moon viewing party, Tanizaki wrote about Kyoko and her ability to dance during a Kyogen performance, led by the master Shigeyama Sengoro. The various antiques which the Yamauchi family gave the Tanizaki’s in token of their friendship are now exhibited in the Tanizaki Memorial Museum in Ashiya.

Junichiro Tanizaki

Tsuki to Kyogenshi

Shigeyama Sengoro

the Tanizaki Memorial Museum in Ashiya.

14

“I have something else to show you,” she says, trying to remember where she put whatever she’s going to show me. After rummaging through a large pile of papers, she produces more memorabilia - videos of Japan in the 1930s.

15

Yamauchi explains that her mother loved photography and filmed a lot of the family excursions with a 16mm Kodak camera. She recently found the forgotten reels in a box and asked NHK to convert them to video.

16

Accompanied by her casual narration, an assortment of images appear on the TV through the scratches and dust of the original black and white film. There are silent scenes of temples, the Gion Matsuri, tea ceremonies, a visiting German circus, boating trips on Lake Biwa, magicians at wedding ceremonies, natural scenery from all over Japan, even the filming of a samurai drama.

17

The lengthy footage is a historical treasure trove of another era as well as of Yamauchi’s incredible past.

18

Her education and upbringing explain her present broad-mindedness and curiosity about the world. In the room she keeps handy two globes so that she can check the countries of some of her visitors. She also keeps a notebook to jot down information she finds interesting in conversation. In quiet moments she enjoys reading, a hobby she developed during childhood to escape the rigid social duties and solitude. Her knowledge of Western literature, especially Russian, is impressive and even today it is not unusual for her to read well past midnight. She also likes watching movies, especially Western ones. “The more action the better,” she chuckles.

19

Such a privileged past as Yamauchi-san’s could easily have made others snobbish or regretful. Whether society girl or landlady, however, she carries no illusions. She’s as happy being with residents as with “older” Japanese women and as comfortable talking about politics as about sumo.

20

Though she is proud of the old photographs and videos, one senses that she would rather not dwell upon the past or talk about herself at length. She is very much in the moment and seems to have embraced her lot in life. “I’ve been lucky,” she says simply.

21

A British friend once said about her, “She’s like a grand matriarch.

22

Indeed, Yamauchi’s network of friends spreads wide and deep. Everyday somebody comes to visit or calls on the phone. One man who she met for only a few hours and has the same birthday as she does has been sending her postcards for the past 10 years. She recently received a letter from a former resident who is now a professor of Japanese art at a college in Los Angeles. Another former Australian resident recalled a summer trip to Lake Biwa with Yamauchi a few years ago. After they fished, she splashed in the water for a while then read a book under the shade of a nearby tree.

23

Our conversation has carried on for hours and the cigarette butts and coffee dregs are cold. We’re both tired and I sense it is time to excuse myself.

24

She gets up carefully and pushes the sliding glass door of the room, which opens into a dark genkan. The house is as old as she is. A dusty portrait of a Renaissance noble hangs above the wooden shoe rack. Yamauchi bows while placing her hands together against the folds of her dressing gown. She says to come visit next week since her son from Osaka will be bringing a video.

25

“I think it’s a Schwarzenegger,” she says.